- Home

- Shani Krebs

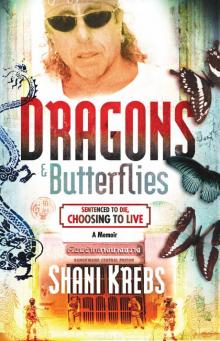

Dragons & Butterflies Page 3

Dragons & Butterflies Read online

Page 3

On weekends our meals were served at a fixed time, which only varied if we had visitors or if Janos decided to braai. Because Janos generally worked night shift, this was the only time that the family ate together.

The hour was fast approaching for Sunday lunch, and then it passed. There was no sign of anybody. Eventually, overcome by pangs of hunger, I decided to go inside to investigate the delay. My mother was not in the kitchen, although the pots on the stove seemed to indicate that lunch was ready. I could hear the faint murmur of conversation coming from the lounge.

Oblivious to the arrival of unexpected guests, I ran into the lounge calling out, in Hungarian, ‘Anyu, nagyon ehjes vagyok’ (Mom, I’m starving). Before I could finish my sentence, I skidded to a halt. There, in our lounge, sat Dantjie’s parents, staring coldly at me. And resting in the centre of our marble coffee table was the Voortrekker wagon Dantjie had stolen. It looked bigger than I remembered it. Mouth agape, I stood there paralysed and terrified at the same time.

Deep in the pit of my stomach I could feel my insides twisting and knotting. Whenever my wellbeing was threatened, my instinct was to run. My brain and body seemed to be at variance today. There was nowhere to go and I knew it. All I could wish for was that whatever my punishment was going to be, that it be swift. The next thing I knew my mother’s towering frame was millimetres from my face. I felt a fleeting sense of relief that it was my mother in a fit of rage and not my stepfather. Heaven knows what would have befallen me then.

Surprisingly, Janos was beaming. He seemed unusually amused by what was going on. I could have sworn his partiality was a sign that, in an absurd way, he was actually proud of me, but I didn’t have time to think this through. My mother grabbed hold of my ear, gave it a sharp twist and violently jerked my head from one shoulder to the other. Was it true, she demanded, that I had broken into the school? She pointed accusingly at the wagon on the coffee table. ‘Is it true that you stole that thing? Is it?’

Still tightly holding onto my ear and jerking my head painfully to and fro, she yelled in Hungarian, ‘Valaszolj nekem!’, pulling my ear even harder, if that was possible. ‘Answer me!’

I looked out of the window, where I could see Dantjie sitting wide-eyed in the rear of his parents’ car, which was parked in our driveway. Although the reflection of the sun on the windscreen obscured my view, his diminutive figure portrayed great shame for having betrayed my trust. Strangely, I felt no animosity towards him. I realised, however, that I could no longer be his friend. I was beginning to learn one of the underlying principles that reflect the true nature of a person.

Since I’d run into the lounge neither of Dantjie’s parents had uttered a single word, but their silent scrutiny made me feel far worse than the torrents of scorn and anger that were pouring out of my mother’s mouth. After being firmly reprimanded and warned that Dantjie and I were never to see each other again, I was dismissed and told that I would be dealt with later.

Once our visitors had left, I was instructed to fetch the rabbit skin from its hiding place. Armed with the largest wooden spoon we had in the kitchen, my mother followed me outside to the storeroom. Before I could even open the door, she had taken hold of my arm and begun to hit me on my tender buttocks with the spoon. I jumped and danced around her in circles, crying out with every lash. The pain was terrible. Eventually, the wooden spoon broke, but this didn’t stop her from exacting further punishment by slapping me around with her hands.

All things considered, perhaps in the end I got off relatively lightly. On Monday morning my mother accompanied my sister and me to school. She met with the principal, returned the wagon and the rabbit skin and apologised for my behaviour. She explained that I had already been punished, adding that, in the event that he had any trouble with me in the future, he had my parents’ permission to deal with me in whatever manner he saw fit.

After this episode, the humiliation and embarrassment of being labelled a thief did deter me from stealing again – for a while. Despite the fact that we learn many of life’s lessons the hard way, I continued to be a difficult child. I constantly misbehaved and refused to comply with the rigid regulations imposed by my parents, although I think, for the most part, they just misunderstood me.

As Joan and I got older, our parents became more innovative with their forms of punishment. These varied from being lashed with a steel coat hanger to being locked inside a wardrobe for hours. The coat hanger was Janos’s favourite device because it inflicted the most pain, leaving bruises and at times drawing blood. But I found the confined space in the cupboard the most traumatic and I feared this punishment more than any other.

My mother, after having to replace many a wooden spoon, introduced a more practical measurement of punishment, which involved very little effort on her part but turned out to be more effective than any of the other more physical measures she and Janos employed in keeping us in line. She would take a soup bowl, fill it to the brim with uncooked rice, and pour the grains onto the tiled kitchen floor. There she would carefully arrange the rice into two mounds on which my sister and I were required to kneel, our arms crossed, for whatever length of time matched the severity of the misdeed. It’s difficult to describe the discomfort and pain of kneeling on rice. Suffice it to say that, when the allotted time was up, I recall having literally to scratch and pick out the grains that had embedded themselves in my skin.

Another punishment Janos liked to use when Joan and I were naughty or our clothes got dirty would be to force us to wear these huge sacks that were normally used for mielies. He had cut holes in the top to make openings for our arms, and, with no clothes on underneath, we’d have to put on these rough, scratchy sacks and walk around in them until he told us we could take them off.

Although my parents were unrelenting in their assertion of authority and exercise of discipline, our lives seemed no different really from those of the other suburban families who were our neighbours and friends. Remember that, in the 1960s, attitudes towards children were archaic in comparison to today’s more progressive outlook, especially among the Eastern European immigrant community.

When I was growing up, if a kid was naughty nobody in his right mind would consider that kid to have some kind of psychological problem that might require therapy. Kids were considered to be resilient and were largely left to develop on their own. It was unheard of for a child to see a psychologist or to take medication. Conditions such as ADD (attention deficit disorder) went completely undiagnosed. Problems at school, such as poor concentration, learning difficulties and hyperactivity were usually regarded as behavioural problems, for which children were punished. From age five I was probably already showing signs of having ADD, but I didn’t think I was any different from most kids that age, and presumed I would improve as I got older.

In all fairness to our parents, who might have failed as our guardians because they lacked some basic parenting skills, and whose attempts to nurture and educate us weren’t always effective, equally there were happy and exciting moments in my childhood, and extended periods of normal family life. There was always food in plenty and we were never short of anything. Janos made good money on the mines. An outsider would probably have said we were an ideal family.

One memorable moment when I was happy as a kid was when I got my first bicycle. Another time, Janos built me a go-kart using a wooden frame and the wheels from my old pram. When we were old enough, my sister and I went everywhere on our bikes. My mother was a gardening enthusiast and our front garden flourished with a variety of indigenous flowers and fruit trees while the driveway was lined with rose bushes – which we crashed into many a time trying too fast to negotiate the turn on our bikes.

Janos had a distillery in which he made a drink called pálinka (like schnapps, and really strong) from apricots. From when I was about five he used to encourage me to drink it.

A few months after the school incident, while out on my bicycle I decided to make a turn at Dantjie’s house, in the h

ope of a chance meeting. To my surprise and dismay, the house was empty and the garden neglected, with weeds growing everywhere. I felt a deep sense of loss, knowing that I would probably never see my friend again.

It wasn’t too long after that that Janos was transferred.

Moving house was a headache. Everything had to be packed into cardboard boxes, and breakable items had to be padded in newspaper. My mom had a collection of rare porcelain dishes, along with other glass ornaments and vases that she proudly displayed in an antique cabinet. My sister and I were required to help wrap these items, which inevitably resulted in breakages. Tensions ran high and everybody seemed on edge, especially my mother, who supervised the whole move. In the interim one of our German shepherds, Nero, the smaller of the two, had contracted rabies and had to be put down. The other dog, Pajtas, was given to the police.

I was heartbroken about leaving our dog behind, but at the same time I was excited at the prospect of moving to another town. And the thought of no longer being required to work in Janos’s little animal kingdom – he reluctantly gave his pigeons to one of his friends – was an added bonus.

We moved to Westonaria, a mining town on the West Rand. Part of the benefits of working for mining companies is that they provide subsidised housing. We were given a brand-new home in a modern housing development on top of the hill about 15km outside town. The roads were not even tarred, so new was this development, and although the house itself was slightly smaller than our old one, my mom was thrilled at the idea of having a new kitchen. This time, our school wasn’t within walking distance and Joan and I had to catch a bus. After school, it would drop us at the bottom of the hill and we would have to walk the distance to our house, which after a long day at school was quite strenuous. I was about six years old.

Although I was not outstanding at school, I was showing signs of being intuitive and an above-average student. It was around the time I was in Standard 1, when a whole new range of subjects was introduced, that I have my earliest recollection of starting to express myself by scribbling with a pen or pencil on whatever surface was available. Drawing was an instinctive force within me. My peers and teachers began to recognise my talents. They were amazed by my illustrations and by my ability to blend colours. I was awarded gold stars for those subjects where we could illustrate our projects and our poems, such as Geography and English. Any subject that required us to draw or illustrate certain functions relating to the subject earned me high praise and recognition.

In the afternoons, while we waited for the bus, we would play games – marbles for the boys, hopscotch for the girls. Another favourite was a game called fly, where three sticks were placed on the grass about a metre apart and parallel to each other. You would run and leap over the first stick but you were only allowed one step before clearing the second stick and then the third. Taking off between the second and third stick, you would try to give a mighty jump to clear the third stick by as wide a margin as you could. Then you would move the third stick to the place you’d landed, thereby widening the distance between the sticks and making it more difficult for the next kid to clear. If you jumped and touched the stick, or landed with two feet or took more than one step in between the sticks, you were out.

One afternoon, when I was still very new at the school, I got so caught up playing fly with some of the other kids that I missed the bus. The bus usually came pretty late anyway, so by this time the school was deserted, and there was nobody around I could ask for a lift home. The only thing for it was to walk home, which I believed I could do even though I didn’t know the area very well yet. All I could think about, though, was my mother’s anger while she contemplated my punishment, so I set off as fast as my small legs could walk. Once I reached the outskirts of the town, the rest of the way was easy. All I had do was walk along two stretches of road that connected to the other at a T-junction. After a while my schoolbag felt really heavy on my back and my legs ached. Then an African commuter bus pulled up alongside me, and the driver leaned across and shouted out to me in Afrikaans, ‘Waar gaan die kleinbaas?’ (Where is the small boss going?)

I pointed towards the hill. Although I couldn’t really see the driver, I could hear him encouraging me to jump on. I hurriedly clambered up the huge metal steps, thanking him, and then I stood there clinging to the railing as the bus jerkily moved forward. Once we reached the T-junction, the driver pulled over again. He was turning left and I was going in the opposite direction. I climbed down the steps and set off again on foot. There was a lot more traffic on this road, and cars whooshed past me in both directions. Then a woman stopped her car beside me and she gave me a lift home. Filled with a mixture of triumph at having successfully navigated the way from school to house and nervousness about my mother’s reaction, I pushed open our front gate. It always made a screaming sound when you opened it, but before I had time to close it behind me Mom came flying out of the house. Tears streaming down her cheeks, she shrieked at me and swept me off my feet at the same time, holding me tightly against her chest with both arms. ‘Don’t ever do that again, Shani,’ she pleaded. ‘Don’t you ever do that again.’

I was not accustomed to either of my parents displaying such affection and I found myself unable to control my own tears. My mother was just relieved that I was home and safe, and for once she didn’t punish me. She was more angry with Babi, my sister Joan, who had neglected to make sure I was on the bus. From that moment on, Babi was given the responsibility of always keeping an eye on me, and, to my mind, she took her newly acquired maternal duties a little too seriously. Sometimes she made my life sheer hell with her bossiness.

After our move to Westonaria there was a distinct change in the atmosphere in our family. My mother and Janos hardly seemed to quarrel any more. Perhaps it had something to do with the highveld air, and we did all spend a lot of time outdoors. It was also around this time that I acquired a passion for building and flying kites.

My stepfather was a keen hunter and he would regularly go on overnight hunting expeditions, returning with all sorts of game, from which my mom prepared her range of lavish dishes. I was about eight years old when, after much pleading, Janos reluctantly agreed to take me with him on one of his hunting trips.

It was late afternoon when we set off, after loading the bakkie with supplies. Janos drove to an area of rugged terrain not too far from where we lived. He parked the van and we got out and looked around. He charged his gun belt with shotgun shells and I filled my pockets with pellets. I was hoping to shoot some rock pigeons with my air rifle. Janos took his double-barrelled shotgun and we trudged along in the direction of some forest, while he took me through the do’s and don’ts of hunting. It was almost dark by the time we approached the cluster of dense trees. Janos instructed me to wait beside a huge decaying trunk that seemed to be the refuge of all sorts of creepy-crawlies, and I didn’t much like the look of it. Sensing my apprehension, he placed his hand on the back of my neck, assuring me that he wouldn’t be too far, and that I had nothing to worry about. His paternal gesture did very little to comfort me. Struggling to hide my indignation at being left behind, I grudgingly accepted that I had no choice but to wait, as apparently my presence on the hunt would be more of a hindrance than anything else.

Janos disappeared into the forest. As soon as he was out of sight, I was paralysed with fear. Holding tightly onto my air rifle, I did a quick reconnaissance of my surroundings, while my vivid imagination replayed numerous possible scenarios, most of which ended with me being devoured by some ferocious beast. I had never felt so scared, alone or vulnerable. I wondered what had possessed me to think hunting was fun. I anxiously looked around for a place to hide and noticed a large boulder a few metres away. It stuck up amid the dense bush and was shielded by a group of wild thorn trees. I thought it would offer a view of the dark landscape as well as provide safety from any prowling predators.

Silently perched on what I now considered my stronghold, my senses adapted to the darkness

, and I took in all the enchanted and mystical undertones that emanated from the forest. The sounds ranged from the cooing of the rock pigeons, the flirting of small birds and the slithering motions of snakes to the musical chirping of the male African cricket. I imagined I heard the steps of some carnivorous animal, too, as well as the distinctive doleful howl of a hyena.

Then, after what seemed like hours, the harmony of nature was shattered by the loud thunder of a shotgun discharging. Birds that had nested for the night blindly rose up and scattered in every direction. I got the fright of my life. I had estimated Janos to be some distance from where he’d left me but it sounded like he was very close by. Despite the shock of the noise, I was also comforted by his presence. Then, at spaced intervals, sometimes firing two consecutive shots, I could hear that he was moving further and further away from me. I was scared, but it heightened my vigilance. I wondered if Janos would ever return.

Eventually, to my intense relief, my stepfather did come back. On his approach he gave a hoot that was a perfect imitation of the low, wavering call of an owl, and at the same time, in his usual bellicose manner, he called out to me in Hungarian.

‘Shani! Hol a fenebe vagy mar?’ (Where the fuck are you?)

Silently I descended from my hiding place. ‘Here,’ I replied nonchalantly, as I strolled towards him. ‘I’m here.’

Janos held a couple of dead guinea fowl and pheasant in his hands.

‘Fogd mar meg ezt es menjunk a francba,’ he said, throwing them down at my feet (Grab these already and let’s get the fuck out of here).

Dragons & Butterflies

Dragons & Butterflies